“To learn what we fear is to learn who we are. Horror defies our boundaries and illuminates our souls.”

Del Toro, Guillermo and Mark Zicree. Guillermo del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities: My Notebooks, Collections, and Other Obsessions. 2013, pg. 66. Sometimes attributed to Shirley Jackson

I’ve always found you can tell more of a society by what they fear and how than what they love. Horror is impulsive and revealing in a truly personal way, while still being tied to broad cultural anxieties. The impulse to shrink, sneer, run away, each are indicative of the person watching but also of the systems around them.

If you were to chart horrors movies by decade, you’d find that monsters follow a clear pattern. Cat People (1942), for instance, follows a dangerous foreign woman who transforms into a violent panther whenever aroused. The film has since been read for fear of queer identity, female empowerment and sexuality, and the rise of working women in the 40s. Rather than rebuking the panther woman, as the film encourages, contemporary moviegoers view the film in light of those politics, discussing how this violent figure influenced other works and scholarship. Films like Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), meanwhile, detail fear of foreign invasion and scientific advancement, both extremely topical per the film’s release.

While cinema is inherently political, horror films outright proclaim that relationship. Scary movies are educational and therapeutic in a bizarre way, even the ones without tidy endings. Metaphor and monster go hand in hand, and what’s especially interesting is the way horror films change outside those original production contexts. What was a site of horror can become a site of sympathy, where the monsters and outsiders of these films are given new lives in the work of modern filmmakers.

Cinematic monsters, or horrors, are complex metaphors which criticize the culture watching the film. Monsters are not simply a reflection of a culture or audience, it’s far more intrinsic. It’s why I can’t help but laugh when I see people complaining about modern ‘woke’ horror, and its use of metaphors. Horror is political, always has been, that is why it’s scary. Some of the earliest horror films, like the Universal horror collection, including Dracula (1931) and Frankenstein (1931), focused on what moved people, not just what made them laugh or feel outraged, but what stayed inside a person, a fear they would bring home with them. You could only see these films for a limited time in theatres, and after that infectious moment, you left the movie with something. Universal Pictures encouraged fear, even circulated shocking stories about people passing out or fleeing during the movie, terrified of both the object of fear (the monster) and the experience of it (the big screen). Combined, monster and big screen, the movie theatre became part lab, part therapy. A place to experiment with what we are afraid of, how, and why.

The sympathetic lens towards sites of horror in film has developed since the Universal days, and we now have directors who grew up on these films (often in later midnight screenings) and relate to these banished figures. Directors like Guillermo del Toro, who has called monsters “the patron saints of our blissful imperfections” (Golden Globe Awards 2017), which puts us in direct relation to the monster. By sympathizing with the monster, we put ourselves in the same position and find the parts of ourselves which we have either learned to manage or the parts we didn’t know about ourselves. Horror films suggest that each of us have the capability to be monstrous, that there is something inside of us, some invisible agent or monstrous thought which could spring out. That suggests that we can no longer distance the monster because it is already inside of us. By going to the movies to look at monsters and horror, we are simultaneously locating, deconstructing, and reinstating social taboos, while also reconsidering what makes us human, or rather, what makes us monstrous.

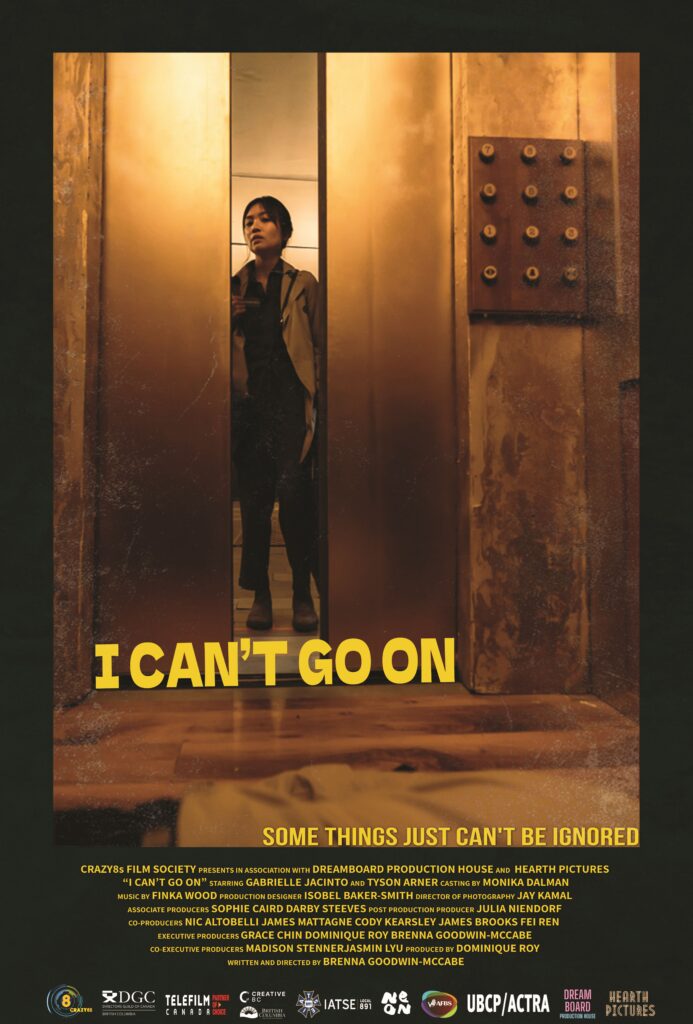

Author’s Note: It’s been a while since my last post, but I have some exciting news! The short horror film I wrote and directed, called “I Can’t Go On”, premieres this Saturday (April 15) at the Crazy8s Gala. It’s about an anxious young woman and the body she discovers in her apartment elevator, left to fester under the heels of her unconcerned neighbours. The project’s a mix of David Lynch, Guillermo del Toro, and Jean-Pierre Jeunet.

Crazys8s is a major Vancouver based film competition, where the chosen Top 6 teams make their film in only 8 days. That goes for all production and post work. It was an intense process, but I am so grateful to my incredible team. We will be hitting the festival circuit next, so be sure to follow us on social media for updates!

Elements of this essay were originally from my article on the Universal Horror Collection, which I decided to expand because I have never officially written an article on the importance of horror cinema. I may return to that subject soon however…