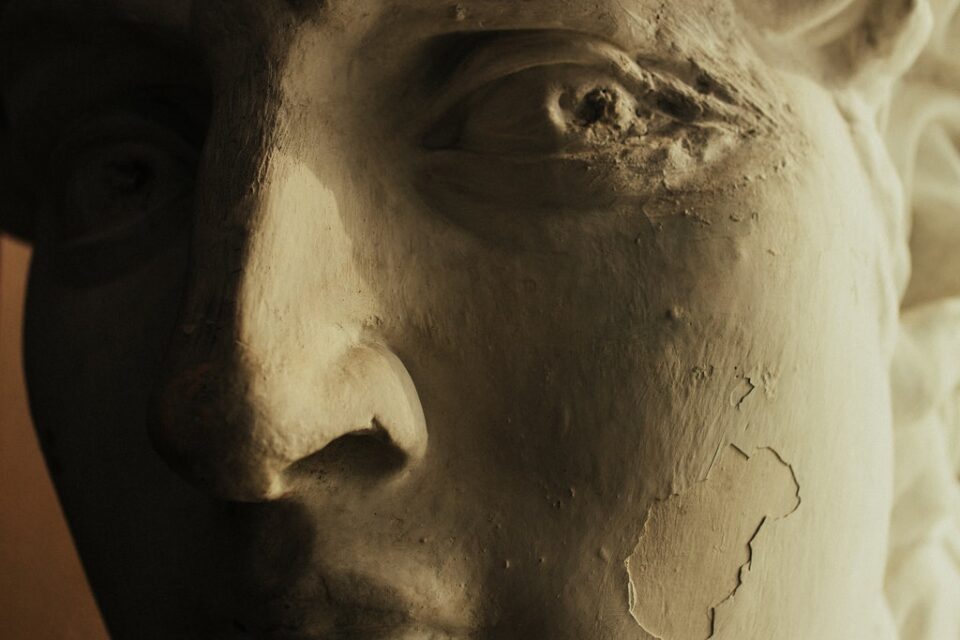

The Ancient Greeks believed that the Titan Prometheus fashioned the first humans out of heavy mud and clay. Ray Harryhausen did much the same when he brought his own mythic monsters to life in Clash of the Titans (1981) and Jason and the Argonauts (1963). You might say that humanity itself is some convoluted form of stop-motion, simply sped up. The Greeks often pose mythology in light of this, suggesting that all mortals and heroes, even the Gods, live at the whim of some unseen and unstoppable Fates, who see the world much like a stop motion artist would. Seeing frame by frame, rather than just the blended and unified final product. Although his work is often called claymation, Harryhausen technically didn’t work with clay. He preferred to work with rubber and metal, so the limbs would be easier to manipulate. Clay is what early stop motion artists turned to, artists like Willis H. O’Brien in his first films, a man who Harryhausen trained under. Harryhausen figures have a certain malleable look to them, which is why so many assume that they are clay. Their movement looks more like warping, like some invisible hand is poking at it, gently warping the clay even with the heat from their fingers. Of course, that is purposeful look, it means that Harryhausen never leaves his work.

Harryhausen characters have a specific style to them, so that you can always tell when Harryhausen is involved with a project, or if a film is paying homage to him. Compare that to an equally recognizable stop motion style like Rankin/Bass, a group who designed films like Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (1964) and Mad Monster Party (1967). It’s the same basic stop-motion method done around the same time, but with a radically different legacy, intention, and art. The most notable difference between the two is that Harryhausen’s animation is often mixed with live action, so it’s an effect, or an entire creature, rather than an entire film. What is disappointing about Harryhausen’s legacy is that his work is often unfairly prefaced as ‘cheesy’ or ‘outdated’, instead of being recognized as a purposeful and stylized form of storytelling. This dismissal is unacceptable, but at the same time, it’s quite telling. Dismissing something means you are comparing it; it’s saying that one thing is bad or less than another somewhat similar thing. Take the stop-motion versus CGI debate, which is a ridiculous comparison because both forms operate with wildly different intentions. CGI is often made to blend in with the film; to look as realistic as possible when interacting with actors. Stop-motion has never been interested in fully immersing its creatures, and that is a crucial distinction.

“As long as man shall walk the Earth…they will remember the courage of Perseus forever.”

I was about 13 the first time I saw the original Clash of the Titans, it was during a Greek mythology unit in my first literature class. I was at the height of my mythology obsession, having just started the Percy Jackson book series that summer. I knew more about mythology at 13 then I did later when taking courses on Ancient Greece in University. Suffice to say I was unbelievably excited to be studying mythology with other people, and even approached my teacher on the first day to ask which myths we would be focusing on, and what texts and authors we would read from. Picking up the first Percy Jackson book made an immeasurable impact in my life, it revolutionized pretty much everything for me, and it’s the reason I began writing. I even wrote and published my first poem that very year called “Forgotten”, about the decaying Garden of the Hesperides, a place I learned about from Rick Riordan’s third book. Clash of the Titans was the first vaguely contemporary media I learned about after Riordan’s books, as my learning had essentially been Riordan, then the translated myths, then the adaptations. I can vividly remember the day my teacher dragged in the TV set, because she was in the middle of warning the class about the film. How it was cheesy, to be ready for that. How it was an old film, and that the mythology was not ‘correct’. It is a cheesy film, but most of that, in my opinion, comes from the acting. The creatures and effects are so unreal that it works, it becomes an extension of the impossible story.

One of the reasons I enjoy Harryhausen’s creations is because the medium works so well with the story of Prometheus. It makes sense that this mythic world is a bit strange, that it moves differently. I try not to speculate on intention in film, because it’s an impossible discussion, but the unrealistic tone here feel intentional. Harryhausen had already made a name for himself by the time he did Clash of the Titans, in fact it was his last film. He had also already worked on Greek mythology in Jason and the Argonauts, which was an extremely ambitious project, and renowned for its terrifying skeleton soldiers. Jason and Clash are sort of twins, in that they belong to the same world, just played by different actors. That world is defined by Harryhausen’s creations, because they are quite stylistically similar. Rewatching Clash recently, I couldn’t remember if both films featured the skeletons, and half believed they would show up to fight Perseus. That is the level to which these films overlap. They might feature different creatures, but those creatures come from the same place, with the same movement.

I honestly forgot that Clash was released in 1981, because it feels like a much older film, one released only a few years after Jason. Audiences even then felt that way, as the film was advertised as an ‘old-school’ corny feature that was a little boring but ultimately worth seeing just for Harryhausen’s effects. It was a success, and remains prevalent, they even remade the film in 2010, and gave it a sequel – Wrath of the Titans – in 2012. Some have called it a Star Wars’ rip off, comparing R2-D2 with Bubo the mechanical owl, but that feels overly dismissive as so many mythology films insert a cute/annoying sidekick. The film makes up a lot of mythology, and also blends it with different literature to make the story feel more familiar to a modern audience. It’s certainly not the first to do this, the Percy Jackson films mixed Hades with the Devil for its audience, and every version of Hercules has done it. It’s a foundational dilemma for most mythology projects, because mythology gets extremely dark very quickly, and that is hard to sell. The story of Heracles is so dark that they’ve changed his name to the Roman Hercules, just to fully remove it from the murder stuff Heracles gets up to, and the reason for his name being Hera-cles. Creators love the 12 Labours, the son of Zeus thing, they can work with that. The reason Heracles has to do the 12 Labours to begin with, not so much. They left that out of the Disney film for good reason, but can you imagine if they hadn’t?

“I spared his life on one condition. That he renounce his curse.”

Clash does much the same in that it needs to make Perseus into a modern and justified hero, while not fully exploring the morals and laws in Greek mythology that make him justified. Perseus is the least terrible hero in mythology, in fact, it’s why Riordan’s protagonist is called Percy (or Perseus). The film must navigate this balancing act, between making Perseus both a hero and relatable to 80s audiences. One way it does this is by carefully choosing when Perseus can kill something or someone. The first time Perseus fights Calibos, he refuses to kill him, instead he just cuts off his hand and humiliates him. He later tells Andromeda that he did this because, deep down, he pities Calibos, even though Calibos is the reason so many suitors have been executed. When he does kill Calibos, it’s only after Calibos has killed two of his companions, which gives Perseus justification. Another example is when Perseus kills a two-headed wolf (named Dioskilos), which he does only after the wolf has attacked and fought other soldiers. Two men die before Perseus can kill Medusa, and that hesitation doesn’t appear in the myth. The Kraken, which is Scandinavian, not Greek, destroys Perseus’ entire kingdom in the first act, threatens Andromeda, and knocks out Bubo in the battle, so Perseus gets to attack immediately. It’s also rather ironic that the film is called Clash of the Titans, because neither the Kraken nor Medusa are a Titan, in fact, no Titan’s appear in the film. Regardless, in each case, there is a series of events that has to happen to establish that these beings are undeniably evil, making it ok for Perseus to kill them. That is a challenge with someone like Medusa, who has become a symbol and patron for abused women.

Clash changes Medusa’s origin story, but only slightly. In the myth, and the later 2010 Clash, Athena curses Medusa, but here, Aphrodite curses her out of jealousy. That might seem like a tiny change, but it does a great deal to the way we view Medusa in this story. In all others, it’s a story about a truly horrific event, and the way people deal with the trauma of that event. Some view Medusa’s transformation as a curse, others as a gift, so she can never be hurt again. The 2010 film argues that Medusa can only transform men into stone, not women, which means that Medusa’s female gaze is a weapon against further abusive male gaze. Here, however, Athena is removed from the story and replaced with Aphrodite, who acts not out of rage or sympathy, but jealousy. This is already framing Medusa in a different light, as someone who chose to anger the Gods rather than being forced to. Perseus therefore has every right to kill her, as before she is an isolated woman just wanting to be left alone, whereas now, she is an inhuman creature who enjoys hunting and destroying men after being rightfully cursed. The change was most likely done because Perseus is accompanied by Bubo, a gift from Athena, and the filmmakers were worried that audiences might get confused by this overlap. Aphrodite being jealous would also suggest that there was some love involved in the incident with Medusa, rather than a perversion of it, which removes this abuse discussion entirely.

“A Titan Against a Titan.”

Symbolically speaking, I find it interesting that Medusa can only be seen through reflections, because otherwise you would be turned into stone. Perseus reminds his companions of this just as they are about to enter her temple, a place much like the one she was cursed for but decorated with statues of decaying stone men rather than statues of the Gods. Perseus tells them that Medusa’s reflection cannot hurt you, which is significant because the audience can see Medusa without turning into stone, suggesting that the film itself is a type of reflection. That any medium that talks about Medusa operates like Perseus’ shield, showing us a slightly inverted but safe version of what she represents. You could say the same for a lot of modern films which talk about abuse and male gaze, as they recreate stories and experiences, but they are always just a reflection. They cannot literally harm the viewer, and the viewer uses this reflection to navigate the threat that is being reflected, what is actually around them and the male gaze that does exist.

Films like Promising Young Woman (2020) turn to mythology like Medusa to talk about male gaze and justice, the protagonist in that film is even named after Cassandra, the Trojan Priestess and Princess. Cassandra had the gift of prophecy, but the curse that no one would ever believe what she prophesized, so she couldn’t stop anything, not even her rape or death. The Medusa we find in Clash has been modeled, literally, with a specific intention, and it’s noteworthy that Harryhausen’s version of Medusa went on to influence every subsequent version. Take the light up eyes, that bright neon green that appears anytime she freezes a person. That became the quintessential image of Medusa, the one we continue to see in media. To say that Harryhausen’s animation is influential doesn’t go far enough. It became the way many later creators came to view mythology, so even when they turned to CGI, they began that work from Harryhausen’s initial visuals.

“Nothing is invulnerable. There must be a way.”

Another dilemma Clash negotiates with is the more human qualities of the Greek pantheon. The Christian God knows everything, is always just, and is mysterious. That is not how Greek Gods operate, they have conflicting views and complicated intentions. Mortals, in many of these stories, are punished by the Gods for things that the storyteller praises. Take Prometheus, the Titan I mentioned in my introduction. He gets his liver ripped out of his chest every day by a hungry eagle for giving humans fire without Zeus’ permission, and Prometheus is a hero in these stories. The humans needed fire, and Prometheus tricked the Gods on their behalf. There is a whole tradition of stories where humans and Gods disagree, and conflict arises. So how do modern Western storytellers work with this, because often times, they are being told to market to a Christian audience, or at least a monotheistic (one God) audience, versus polytheistic (multiple). These films tend to label a few Gods as good and others as evil, and then give the hero a reason to fight against certain Gods while not angering others. This way, the film can appease the monotheistic out there, showing that this system has its problems that even the protagonist disagrees with, while still staying ‘true’ to the mythology.

That criticism has become even more apparent in recent media, like the God of War video game series, where you play as Kratos, a Spartan demigod who wants to brutally kill the Greek pantheon. Even the 2010 Clash film portrays the Gods as distant and vengeful beings who distrust humans, even those they parent. This all comes from the fact that these stories place the hero in defiance of a God, which is impossible and unjustified if you are coming from a Christian perspective. Imagine if one of the Christian prophets suddenly declared war on God, and not a symbolic kind, a literal war with a visible and singular entity. That happens all the time in Greek mythology, with varying success, and varying horrors. The challenge in the original Clash is to make Perseus justified while still angering a God, and thus suggesting that one of the Gods is wrong and that a mere human isn’t.

“The ring of the Lord of the Marsh. The pearl ring of Calibos.”

The original Clash successfully does this by inventing a new storyline, one where the Goddess Thetis has a son named Calibos. Thetis is a real figure in mythology, but her son is Achilles, one of the great and impervious heroes. She is known for being protective of Achilles, for dipping him at birth in the River Styx, all but his heel, and that protective nature translates into Clash. Here, her wrathful son Calibos offends Zeus, who brutally curses him, and she tries to avenge her son with a curse against his betrothed, Andromeda. Calibos is not a mythological character, he is a Shakespearian figure who appears in The Tempest, there named Caliban. Shakespeare borrows a lot from mythology, whether be literal characters like Hippolyta in A Midsummer Night’s Dream or just multiple references to different myths. I have dedicated a different article here to his use of Ovid’s Philomela in the play Titus Andronicus, if you are looking for more on this. Clash simply continues the transaction between Shakespeare and mythology, making it double sided. Here, mythology borrows from Shakespeare, who in turn borrows from mythology.

Calibos is essentially the same character here as he is in The Tempest, and there is this implied sexual violence between him and the hero’s love interest, first Miranda now Andromeda. There are some problems with this overlap, however, as the portrayal of both Calibos/Caliban in Shakespeare and Clash are stereotyped and even racist. There is a horrible legacy of blackface in Shakespeare performances, shows like The Tempest, and Clash turns to it. Calibos is played by a white actor in blackface, with a fake tail to make him seem like a lizard. It’s unclear what Zeus transform him into, possibly a satyr, but the result is that he was white but is no longer and has been banished from Joppa as a result. It doesn’t help that Joppa is situated in modern day Israel, yet every person in the entire film is very white, except for Calibos, who was before Zeus. The 2010 Clash film clearly recognized this and changed their storyline so that Calibos is now Perseus’ furious stepfather, Acrisius, and the makeup looks like he was split down the middle, no lizard tail, and everyone in the film is still white.

“What if courage and imagination became everyday mortal qualities?”

The distanced shots of Calibos are the only ones which actually show him as a monster, akin to Medusa or the Kraken, as Harryhausen has animated his tail to lash out, much like the whip he carries instead of a sword. There is a visible difference whenever the film switches between live action and stop-motion, and it can be jarring, but I think that is for a reason. These stop-motion characters are not realistic, but neither are the characters to begin with. It shows that whatever the character is doing is not something the filmmakers could get an actor to do, and so it takes on this different and impossible movement and timing. Rather than just shining a bunch of light or changing the music to show that a character is powerful, it literally reorganizes the natural world so someone like Perseus can jump on Pegasus and fly about. It’s different than what we see in more modern superhero movies, because here, the film is acknowledging that whatever the character is doing is categorically impossible. It’s the ultimate don’t try this at home move, because there is this sort of removed nature to it all.

What is funny is that Harryhausen’s work has been referenced in light of that in a few different projects. The Percy Jackson books reference Harryhausen a few times, and the fandom often visualizes Hades’ Skeleton Soldiers as the ones which appear in Jason. There is a remarkable episode of Gravity Falls (2012-2016), called “Clay Day”, where the characters meet Harry Claymore, a clear parody of Harryhausen. They learn that he didn’t use stop-motion, because it took too long, and instead became a Victor Frankenstein type and literally brought these clay creatures to life and has been hiding them in his studio ever since computer animation became standardized. The episode actually uses stop-motion animation for these creatures, just to signal that they are visually and physically different than the show’s normal animation, and that their ‘malleable’ clay appearance is just as important as the works they appeared in.

The episode also acknowledges that they are scary looking, because of their sort of distorted pace and appearance, but also because its scary to think that these unreal things could suddenly appear in our world. If CGI belongs to our world, trying it’s best to fit in with actors, then stop-motion imposes a new world onto ours. It’s the reason the 2010 Clash is not as interesting as the original, as it’s effects just blend in with every other action monster film. There is nothing remarkable about it, and often the actors move so quickly through the CGI that it just becomes blurry, and you don’t actually have a chance to take in the design. It fills what needs to be there for the story to move forward, but it tries to hide the fact that it’s made in post-production. That is different than the original, it’s different than announcing that painstaking task of going frame by frame and changing the tiniest position and then speeding it up, but not so fast that the audience could forget that it’s stop-motion. The artist is still in the frame, there is no attempt to hide their work.

“What if there a more heroes like him?”

Perhaps this is a little presumptuous, but I think we are moving into another mythology heavy era in media. They tend to come in groupings, there was a ton in the 60s and 90s, like Xena: Warrior Princess (1995-2001) and Hercules, both the Disney film (1997) and the live action show (1995-1999). The first Percy Jackson film they made came out the same year as the Clash remake, 2010. Now we have a Lore of Olympus animated show coming, and a new Percy Jackson series, in fact, they are filming in my city later this year. I am beyond excited for the project now that Riordan is involved as executive producer, it feels almost as exciting as when I was 13 and ridiculously pumped about mythology. It’s crazy to think that the place I live in will be transformed into this landscape. I used to do that as a kid, playing Greek mythology with my friends and running through the forest with nerf swords. Vancouver won’t play itself, but it never does. They filmed some of the 2010 film here as well, but as I’ve discussed before, that film is the only time I have ever wanted to leave a movie theatre.

You can actually pinpoint the day I went, because I was at that annoying age of posting my every random thought on Facebook. I suppose I have a blog for that now. I was constantly writing about my excitement for the movie, every day in the week before. Then a heartbreaking day of silence, I was apparently too upset about the film to report. I only set myself up for more disappointment when I began posting about my excitement for the Clash film, and how I hoped it would be better than the Percy Jackson film. It was technically better, so I wasn’t completely off for that one. That aside, I am excited for the new streaming series, and I kind of hope they return to some of the visuals that defined these ‘classics’, maybe just a few Harryhausen inspired skeletons (though inspired skeleton sort of sounds like a band name). I’ve mentioned this on the blog before, but I am a filmmaker, and it’s a dream of mine to work on a mythology related project. Two of my earliest films, back when I was in high school, were an adaptation Psyche and Eros and then a Quentin Tarantino inspired version of Euripides’ Medea. I am currently trying to be more involved in the Vancouver production community, to meet other creators while also working on my own short films. Maybe I’ll be lucky enough to get to work on this Vancouver project in some limited capacity. I’ll have to keep my eyes open because I would love to facilitate a story that defined so much of my life.

Side note, if you are involved with the Vancouver film community, whether in production or just as a movie lover, feel free to shoot me a message (email@youremindmeoftheframe.ca)!

I also published my first article with Bored in Vancouver this week. It’s all about one of my favourite local movie theatres. You can read it here.