A flashlight moves across a dark desert road. It sweeps the sand, across faded footprints, until it stops on an empty purse. Beside it, a small handkerchief blows over, almost like the faint light pushed it aside. The spotlight then pans up a car door to reveal two unidentifiable bodies, a man and a woman, their faces turned from the camera. We cut to a police officer, stunned at this horrible sight and its seeming randomness. He lowers his flashlight, almost in respect, and quietly curses the serial drifter. A terrible killer who thinks of only himself, and whose random movement is equally unprecedented and unacceptable. Then again, this terrifying figure isn’t the only thing hitching a ride in the film.

Film noirs like The Hitch-Hiker deal with deeply troubled characters, particularly those who feel entirely detached from normative society. Despite their nuanced and existential subject, the genre is fairly simple, at least morally speaking. The good guys, however chaotic they initially appear, end up doing the ‘right’ thing and the bad are always punished. These films are more interested in dichotomies like good and evil, justice and injustice, rather than the blur between these issues. They likewise show these issues in literal black and white, another dichotomy. What’s more, these films often focus on similar character types, to the extent where you can predict how a character will behave based on earlier film which feature their character type. For example, there is the unmistakable bad guy, someone who is on the run and is unhinged from society. This character always dies at the end of the film or is punished and locked away forever. There is also the chaotic good character, usually the protagonist, who is slightly disheveled but ultimately does the right thing.

My favourite film noir type, however, and perhaps the most famous, is the femme fatale. Although femme fatales exist in other genres, particularly in literature as ‘fallen women’, their name belong to film noir. A femme fatale is a dangerous and sexy woman who lures men to their deaths while also actively rejecting ‘proper’ and ‘docile’ femininity. This figure is synonymous with film noir because both arouse from similar anxieties. Film noir arouse during the 40’s and 50’s, although it continues to adapt in contemporary cinema. It is one of the clearest examples of how a society can so decisively reflect their media, and how you can measure cultural anxiety through film. I would argue that film noir arose from a deep pessimism and fear around women and change. Men had just returned from WWII, already changed and traumatized, to find that life was different. Women were far more independent and employed than when they left. The world had moved on and progressed without them, almost as though it did not need them. Whatever individualism they lost in the war simply shriveled at home. Film noir is a direct response to that insecurity, as it examines pessimism, fear, death, and just general existentialism towards this displacement. It is important to note that this insecurity had sexist, racist, and violent consequences, and film noir is just as much a reflection of that anger as anything else. The femme fatale became a commentary on women who worked, often a very harsh commentary. There are some positive femme portrayals in film noir, but they are hard to come by. Most times, these independent women are punished, killed, or domesticized by the end of the film. They are not in every film noir, but they are a definite characteristic of that genre.

You can imagine my surprise when I came across a female directed crime film noir from 1953, one which starred an exclusively male cast. There are no femme fatales here, but it was directed by a woman who was well-known for playing such characters. Finally, I thought, the classic femme fatale actress gets creative control. I would soon realize that something even more interesting was happening in this film. A woman isn’t physically present, rather, she is another hitchhiker, traveling along with these violent men and quietly commenting on how inconvenient and ridiculous their insecurities are. She is on the other side of the frame, holding the camera and choosing the shots, the very angles of this power struggle. She’s everywhere, and the film’s true unspoken hitchhiker.

“You Make Pretty Good Targets from Where I Sit.”

Ida Lupino directed multiple critically acclaimed films, and was a talented actress, known for her femme fatale role in They Drive by Night (1940). She also directed Outrage (1950), a sympathetic film about young rape victim (although the word rape is never used), and “The Masks”, one of the most famous Twilight Zone episodes. I decided to focus on The Hitch-Hiker, because it has this strange unspoken texture to it. The film is essentially an ongoing discussion on the practicality and use of film, as well as the role of the female victim in film noir. I cannot emphasize enough how unusual it is that a woman directed what 50’s Hollywood considered a ‘man’s film’. Other films directed by women in this era are quite rare, as they were often relegated to directing ‘women’s films’, like romantic comedies, or were just uncredited. This film, however, makes it abundantly clear that it is a man’s film, and that is it only interested in men’s fight for survival. But, as I will go on to suggest, it is also about male insecurity and loss of power. There may be only one woman in the film, a dead body shown for a few seconds, but the lack of women is an important feature. The director’s presence is everywhere, as everything in the film is a warning about serial killers, but likewise a warning about masculine insecurity, and the countless lives that stupidity can take with it.

Before the film officially begins, we get an opening paragraph. The first line reads, “This is a true story of a man and a gun and a car”. That single sentence summarizes everything about the film. It’s only interested in a man, his gun, and the car he steals. With his gun, this man is truly dangerous to anyone decent enough to offer him a ride. The film is technically about two men who pick up a hitchhiker and then find themselves at gun point, forced to drive across Mexico, without knowing when or where this assailant will kill them. Beyond a literal description, this first sentence directs us to something especially important. This is a true story; it could happen to anyone. However, while suggesting that anyone can be a victim, this sentence likewise specifies that only a man could be the attacker in this situation. This line is very vague about everything other than gender. The attack could happen anywhere, at anytime, but the attacker will always be a man with a gun.

The next line of the opening text continues this ambiguity, noting, “The gun belonged to the man. The car might have been yours-or that young couple across the aisle”. This line makes a few major assumptions. First, that you have a car and would be willing to pick up a hitchhiker. Second, that you are in a theater watching this film, and that there is a couple near you. This assumption directly involves the viewer, although it has changed contexts since 1953. I certainly did not see the movie at a theatre, and so the word “aisle” made it seem like all recently married couples, those who just walked down the aisle, might face a threat like this. The ‘you’ similarly signals that this film has a practical use, and that it is required viewing for all.

This practicality makes sense as Lupino’s film is based on an actual occurrence, a real killer who targeted anyone who would pick him up. This killer became quite well-known and had been executed only a year before the film was released. The film’s main purpose was thus to warn people about drifters, the kind of ruffians who didn’t belong to any family or community. What is interesting is that both Roy and Gilbert, the two victims, are also drifters. We first meet them as they are discussing where to drive, as both have lied to their wives and don’t know where they want to go. When the killer brings this up later, both characters look away, ashamed. There is some suggestion that the men want to cheat on their wives during this trip, but for argument’s sake, the main issue here is that they want to be aimless. They don’t want to be tied down to anyplace or anyone, which obviously does not happen. They in fact get tied to the hitchhiker and must do everything he says.

“For the Facts Are Actual.”

Lupino’s film conveys something important about the use of cinema. Since the first camera was developed, critics have debated why recording people is important. Some early critics, even Virginia Woolf, suggested that the main purpose of cinema and the camera was to record the world in a scientific sense, almost like a diagram or illustration. It certainly was not considered an art form, more like a practical aid. Being a painter or sculptor took skill and were thus art. Holding a camera was different. The alternative position, the one we share today, is that cinema is a form of entertainment and storytelling, which puts The Hitch-Hiker in a strange place. It is an entertaining film, yet as the opening text suggests, the narrative has a moral and judicial function which is more important than this entertainment quality. It announces itself as a commentary and lesson within these first moments, and that emphasis focuses on masculinity. A man with a gun. Why does have a gun? Because he is insecure and has a power complex. Should he have a gun? Obviously not, something has gone terribly wrong, but unfortunately that is the current situation.

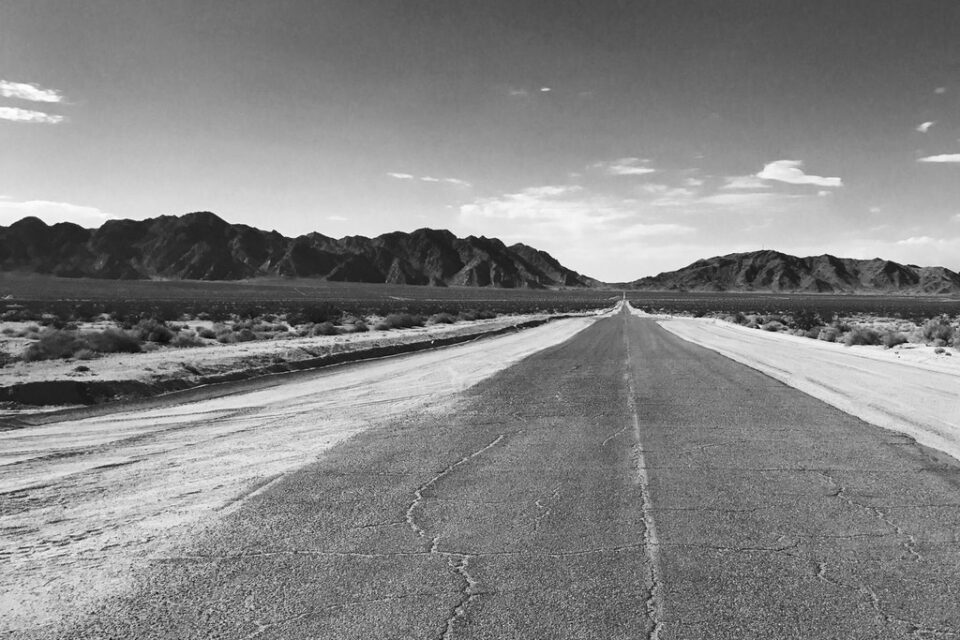

It is noteworthy that the film takes place in a desert, versus other film noirs, which often take place in cities or at night. Most of this film occurs during the day along different hills and highways, just to further emphasize how alone the characters are. This space again stresses how dangerous drifters are, people who are not just unattached, but uncomfortable in a community or city. For example, the three men (the victims and their assailant) pass through multiple towns and occasionally stop for supplies. Most of the people in these towns only speak Spanish, which is a problem for Emmett (the hitchhiker) as he can only speak English. He is terrified that his two victims will somehow get a message out to someone without him knowing, and so he tells the men to either stay totally silent or to only speak English, even though many of the people they encounter have no idea what they are saying. This of course makes the men stand out more, as people keep reporting the men to the police because they are strange group of Americans who just keep gesturing at things and refusing to look people in the eye, as one man stands to the side, hand in pocket, while yelling at the other two. There are also a few scenes which are entirely in Spanish, with no subtitles. The switches in language here and the long silent sequences emphasize two things: language and sound. The issues around what is said and unsaid, heard versus understood, are everywhere in this film. The main characters are terrified of saying the wrong thing, while Emmett is terrified that they will outsmart him. Both groups try to keep things from one another in response to this insecurity. The men don’t tell Emmett about their plans to escape (obviously) just as he doesn’t tell them when or where he plans to kill them.

I want to focus on the first scene of the film, just to avoid spoilers entirely. The hitchhiker is initially presented as a mystic figure. We don’t see his face until after he kidnaps our protagonists, but we also don’t see his victims’ faces. It’s as though his rambling nature infects the people he travels with, as he abandons their bodies on random roadside and steals their wallets. He dehumanizes them, and the camera reflects that by not showing any defining features on the victims. The first victim is an unseen woman, and in fact, her scream is the first human sound in the film. We then see her purse fall to the ground before a hand reaches down and grabs her wallet. The camera follows the attacker as he leaves the scene, tracing after his dark shoes as he walks off. We then pan back with the flashlight, described earlier, and see the two slightly obscured bodies. When the flashlight finally hits the car, we don’t see any blood, just the two victims, and their turned heads. This scene illustrates that the film focuses on the threat of violence rather than the violence itself. It initially presents the threat as though it’s inevitable, but the violence never arrives, or if it does, we do not see it.

The only face we see in this entire opening sequence is the police officer, which signals that he is a human voice of reason, and that justice will eventually prevail and be the only figure willing to track or even witness this violent spree. And yet, even this figure is insecure of his environment. He has just come across two dead people and there is a moment of shock and terror in his eyes. Like the other male figures in the film, he doesn’t know how to respond in this powerless situation. It’s not like he can bring these people back to life and protect them. Something senseless and beyond him has happened, and all he can do is report it to his superiors. Emmett faces something similar, as he later asks his two prisoners if they are married, as he is not. One report which was often made of the killer who inspired the film is that he was isolated and had a troubled family life. That comment became an explanation for why he was so terrible, and it was repeated multiple times, as though the public needed to know how someone could be so disconnected. In response to being so powerless in life, the hitchhiker in the film constantly barks out orders and detailed instructions while threatening the men, as though he is trying to install some control in his life. Keep in mind, he has no idea who will pick him up, who will be his next victim. His control and power come from a weapon, nothing else. He is unremarkable, unskilled, and uneducated. You can feel that stupid insecurity everywhere in the film, even in his male victims, who are insecure about their situation, marriages, and control in general.

“What You Will See in the Next Seventy Minutes Could Have Happened To You.”

I believe that the film’s focus on male insecurity highlights a broader commentary on 50’s society and film noir. The female victim, the first human sound in the film, dies. There are no other women, no room for them in this male-centric power trip. They don’t have the opportunity nor luxury to be insecure, and the film kills them off before they can. There is one scene with a young girl, but even then, she is just dangled there as a possible victim. She doesn’t have any lines and we never see her again. We are instead left with these three men, each completely out of their depth and unsure of everything. Just to summarize, Emmett is insecure about his lack of education, language, and home life, while the two other men are insecure about their immediate situation and home-life. Likewise, the all-male police department spends most of the film utterly clueless about where the three men are, and their traffic stops are useless. They only discover what is happening later in the film, as prior to that point, they are busy with damage control.

Given that Lupino was a recognizable femme fatale actress, and considered an ambitious and outspoken woman in Hollywood, it feels like this film is a critical and self-conscious portrayal of film noir, just not directly. Much like the meandering trek in the film, the commentary weaves itself into its insecure characters. There are times when it is quite apparent, other times it is more nuanced. Regardless, The Hitch-Hiker is about more than just a man and a gun. It’s about the threat that combination holds, and why it should be questioned, analyzed, and stopped.