Repo! the Genetic Opera (2008) was arguably my first horror musical, or at least, it was the first horror musical I ever had a personal connection with. I grew up in the suburbs, so films like The Rocky Horror Picture Show (RHPS) were not shown locally, and their fandom felt rather daunting because they were so established and extensive. Although I love RHPS now, having attended actual screenings, I never felt like I belonged in that group growing up. I was also nervous that I would perform the film wrong, mess up a cue by throwing rice at the wrong time, or something like that. Or just be forced to go to a screening on my own. Repo was different. It was a younger film and certainly one of the first horror films I genuinely enjoyed.

Repo was the first of three horror musicals created by Darren Lynn Bousman and Terrance Zdunich. Soon after Repo came The Devil’s Carnival (2012) and its sequel, Alleluia! The Devil’s Carnival (2015). I believe that this unofficial trilogy is the clearest example of a horror musicals, as each film uses music to enhance their horrifying and occasional blasphemous subject. They were also created with the conscious intention of being read as a cult film, and all the associations that term elicits. The films actively participate with the legacy of RHPS and other cult horror musicals, primarily through their fandom and casting decisions.

“Don’t You Dare Touch Your TV”

Like RHPS, Repo was originally a stage play, created by Zdunich and Darren Smith in 2002. The stage production was marketed as a modern opera, one which drew from the well-respected classical genre while also enhancing its more dramatic and horrifying elements. While opera is regularly dismissed by modern audiences, labeled as droll and outdated, we see the same level of theatrics and death in contemporary horror film. I once watched an opera where a woman was brutally stabbed, suffered a miscarriage, was stuffed in a trunk for most of the second act, and then managed a 5-minute aria before gracefully dying. This is the extreme level to which Repo was inspired.

Repo the play became an unexpected sensation and began selling out shows in various clubs. Eventually, director Bousman heard about the production and proposed a film version, an opportunity which arose after he had directed Saw II and III.

The film was not a mainstream success, but it toured across North America and did well as a participatory film. People would dress up, sing along, and form shadow casts, performing underneath the screen and acting out the scenes as they happened. Repo became a cinematic pilgrimage, which is why the Devil’s Carnival series was created.

While Repo had gained this fandom, it wasn’t enough to financially warrant a sequel, though both Bousman and Zdunich wanted to create one. Unfortunately, to create Repo, the creative team had been forced to sign over their idea to the production company, which meant they could not make a sequel without their funds and involvement. Because they could not return to Repo, the creative team had to come up with a new idea, something which would appeal to their devoted fanbase while also not infringing on their legal agreement. On the heels of this treacherous contract, Zdunich and Bousman created The Devil’s Carnival, a film is ironically about a contract with the Devil. Whether or not these events were connected, it is entertaining that a deal with the industrial devil created Repo, while Devil’s Carnival was created in spite of that contract.

The first Devil’s Carnival film reunites many of the cast members from Repo and returns to its nihilistic yet comedic tone. While the subject matter in Repo had been taboo, the material in Devil’s Carnival is blasphemous, but it technically comes for a long tradition of literary blasphemy. It is really just a continuation of works like Dante’s Inferno, in that it examines what it means to believe in hell, what hell looks like for each person, and the politics around hell and the Devil. The second Devil’s Carnival goes even further than the first by portraying Heaven as a violent authoritarian state filled with propaganda and fear. Together, the films suggest that people are inherently flawed and that the two-layered divine system is inherently problematic.

The Devil’s Carnival also toured North America and had a similar response. This was enough for the second film to have a larger budget, full cast, and be full-length. However, like Repo, both Devil’s Carnival films dealt with some logistical and production issues, and ultimately were not as successful as the creative team had hoped. A third Devil’s Carnival is not currently in the works, even though the second film ends with a cliffhanger.

However, Repo and The Devil’s Carnival has a combined fandom who continue to participate with screenings. People still cosplay as the characters, create artwork based on the projects, and perform the songs. It helps that many of the actors in the films are musicians, as they bring their own fandoms with them. As a result, Repo and Devil’s Carnival has an amalgamated cult status, one which blends multiple backgrounds, genres, and interests. As an example, the films appeal to people with musical theater backgrounds, horror fans, rock, opera, and heavy metal listeners, and even readers of classic literature.

Casting the Opera

Zdunich and Bousman’s films remain topical because of their purposeful casting. Each of the projects incorporates the reputation of their actors, and in doing so, connects the actor’s more recognizable work with the horror musical. For instance, Repo stars Anthony Steward Head, of Buffy the Vampire Slayer fame, and Sarah Brightman, the original Christine Daaé in Broadway’s Phantom of the Opera. This links Repo with more famous and recognizable works and fandoms, particularly the Once More, With Feeling musical episode of Buffy. It is no surprise that Head and Brightman play similar characters in Repo, as their new role represents a running commentary on these earlier horror musicals.

Head plays a worried father who is willing to sacrifice anything to protect his daughter. Brightman plays an ethereal opera singer at the command of a vicious, controlling, and all-seeing antagonist. These are the same situations found in Buffy and Phantom of the Opera, and so at first, it seems like Head and Brightman are playing the same character. However, Repo additionally challenges our expectations of these characters. These actors are not simply repeating their earlier works, they are playing a corrupted version of that character. Head is a serial killer who makes several questionable choices in the film, and it is ultimately revealed that he poisoned his daughter so he could ‘protect’ her from the world. Likewise, Brightman is murdered mid-performance after plucking out her own eyes. Her character might be a version of Daaé from Phantom, but one whose escape from the Phantom is soaked with her own blood rather than other people’s.

In addition to Brightman and Head, Repo’s casting decisions add a further layer onto its commentary about capitalism and greed. The cast includes Paris Hilton as Amber Sweet, the wealthy daughter of Rotti Largo, the president of the GeneCo empire. Amber is a distorted version of Hilton, which makes it seem like Hilton is in on the joke about her persona. For instance, the films centers much of its criticism about Amber on her terrible singing. Although Amber can constantly modify her body, she cannot change her voice. When Amber’s face falls off mid-performance, the film signals that her body is too unstable, both because of her addiction to Zydrate and her need to become a different person. It suggests that Amber’s internal state is rejecting her, that her intake of drugs and new body parts has made her volatile. Although she tries to be multiple people, by this scene, she is barely one person.

While Hilton has been criticized for her acting and singing in the film (unjustly), she remains one of my favourite parts about the movie. Her presence introduces all the associations we have with Hilton, and in doing so, enhances Repo’s discussion on wealth and privilege. I disagree with the suggestion that Hilton was unaware of this reference, as I believe she uses her persona in the film (and in pop culture) in a very purposeful and self-aware fashion. If anything, my one critique of Repo is its exploitative tone around Amber, just because it focuses primarily on her sex appeal rather than her emotional instability. I have also read that Hilton was uncomfortable on set, and additionally that these fandoms have occasionally been quite toxic and even abusive. I don’t have personal experience with that, but I think it should be noted. I’ll spent a little more time with this issue shortly, because the way these projects frame women, sexually and violently, warrants further discussion.

Casting the Sinners

Just as Repo had actors return to their most famous character traits, Devil’s Carnival manages its cult status through several famous actors. The first film has a few actors from the Repo universe in addition to some alternative rock singers. The second film includes multiple actors from famous rock musicals. This includes Ted Neeley from Jesus Christ Superstar (side note, he is possibly the kindest person I have ever met), Barry Bostwick from RHPS, Adam Pascal from Rent, and David Hasselhoff from the stage production of Jekyll and Hyde. Each of these actors play a version of their most famous role. For instance, Neeley is one of God’s disciples and a publicist/band leader, a direct relation to his role as Jesus. There is even a moment when Neeley walks into a room and asks, “What’s the buzz, tell me what’s happening”, a lyric from Jesus Christ Superstar. Likewise, Bostwick plays a voyeuristic character reminiscent of the themes in RHPS, while Pascal plays a troubled and appealing romantic interest. At the same time, we see these familiar actors in new and unfamiliar contexts, as Bostwick plays a villain who tries to blackmail Painted Doll because of her lesbian relationship, and Pascal ultimately forsakes Painted Doll to save himself. This inverses the sexual liberation found in RHPS and the love and fidelity demonstrated in Rent.

The Devil’s Carnival similar reframes some of its musicians, particularly Tech N9ne, who plays a powerful librarian in the second film. A quiet librarian is the exact opposite of Tech N9ne’s persona, and so we go into the film with a certain set of expectations around these actors and the kinds of characters/personas they are usually associated with. That expectation comes from us, so when the film challenges these expectations, it deconstructs our preconceptions of these actors and characters. This means that the films take our expectations (our inside/internal thoughts), projects them onto a new but familiar figure, and then drastically changes that figure and their and world (the outside). The boundaries around inside and out, both in bodies and in fashion, are fundamental to Repo and The Devil’s Carnival, which suggests that their casting is just one of the ways the films involve this discussion.

The Politics of Inside and Out in Repo

What’s interesting about watching Repo today is that it is hard to escape from what it says about modern politics. While the Largo family was modeled off the 15th and 16th centuries Borgia clan, they also relate to the Trumps, which makes the film’s discussion on incest and capitalist even more relevant. In fact, I can’t stop thinking about how the Largo clan mirrors the Trumps, and I think that is a sign of how important Repo is. It might focus on a post-apocalyptic world, where human lives are nothing compared to corporations and the greed of a few horrible people, but it certainly mirrors our world. Not to mention the film’s discussion on drug addiction, plastic surgery, and the American health care system. Again, the film distorts these issues and introduces new problems, but these distortions are not far off. For example, the Repo Man, played by Head, reclaims organs from people who cannot keep up with their payments. By focusing on the moment of extraction, and the individual organs pulled by the Repo Man, the film fixates on an extreme, horrifying, and disgusting medical practice. However, it does so while also drawing parallels to the American health care system, specifically the way it positions low-income families. The film seems to suggest that while the Repo Man is a terrible figure, he is not far off from what is already happening in the States, where people are forced to compete in popularity contests on Crowd Funding websites just to pay for hospital bills. The film is thus a cautionary reflection of our modern world.

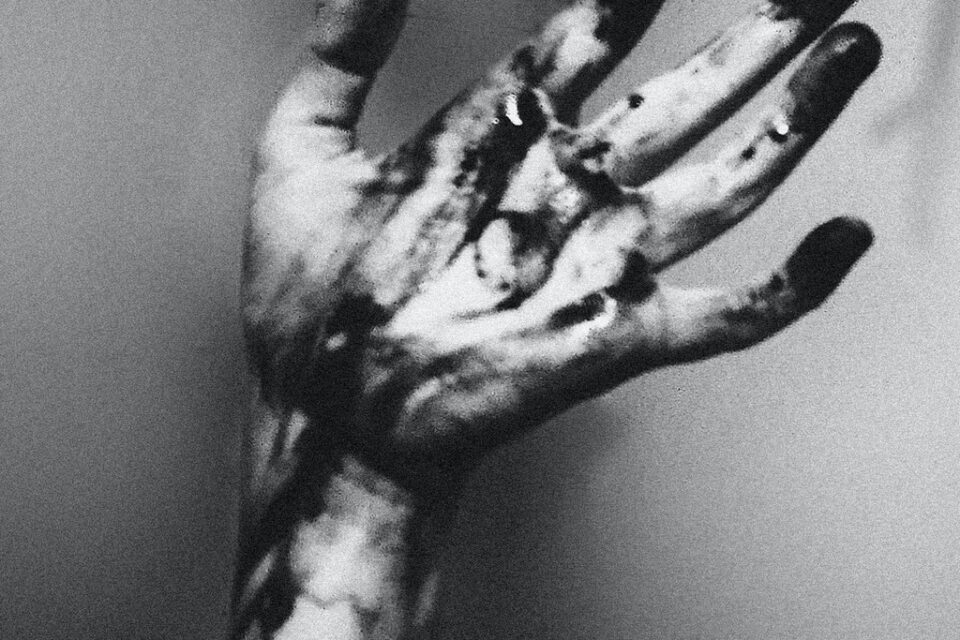

Repo has a sick sense of recycling, as organs and faces move between people. Even the drug Zydrate comes from recycling, as Grave Robbers steal it from the bodies who underwent surgery. All the characters in Repo are in someway connected to a manipulated and recycled human body, whether they are modifying themselves, wearing the faces and parts of other people, dying from an internal disease, or dissecting people. Body modification is a form of recycling in the film, as people undergo surgeries to be beautiful on the inside, and the Repo Man literally modifies bodies by ripping out people’s organs.

The film thus focuses on the politics around in and out, and the relationship between the two. We can read this as medical, sexual, or even emotional. Amber is a good example of this emotional reading, as her concept of self is constantly shifting depending on her modified body. Because she is constantly changing her organs and appearance, Amber hopes that she can also change something greater about herself. It is a bit like the Ship of Theseus: if Amber replaces all her parts, at what point does she stop being Amber?

Characters like Amber and Shilo are so unstable because of their genetics, the little details inside of them. The film argues that our genetics constitute a form of infection or even possession. Genetics control your story in ways that you are unaware of, and they quietly dictating our behaviour, our vulnerability, and our sense of self. For example, Shilo is the daughter of Nathan, the Repo Man, and his dead wife, who he claims died from a mysterious illness but actually died because Nathan gave her the wrong medication. Because of this trauma, Nathan is obsessed with protecting Shilo from everyone, going so far as to poison her and lie so she stays at home with him. He views her as an extension of his wife, an Edgar Allen Poe style living portrait which haunts and drives him insane. He convinces Shilo that the outside world is toxic and deadly, and that she will die if she goes outside for too long. This is another demonstration of the film’s emphasis on inside and out, as the environment has a causal relationship with Shilo’s health.

Nathan is not the only one to collapse Shilo with her dead mother, as Blind Mag (Brightman) and Rotti (Paul Sorvino) do the same. Blind Mag is struck by how similar Shilo is to her mother, and like Nathan, she believes that getting close to Shilo will in some way reconnect her to Shilo’s Mother. There is even a moment in Blind Mag’s song “Chase the Morning” where she shows Shilo a projection of her mother using Mag’s voice. Likewise, Rotti thinks of Shilo in a similar light, although he is actually responsible for her mother’s death. Shilo’s mother, Marni, was engaged to Rotti before she met Nathan and ran off, and he had her murdered while also framing Nathan as revenge. Rotti thinks of Shilo as a version of her mother and as the daughter he was supposed to have. When he invites Shilo to the opera, he gives her a dress her Mother once wore, in fact, the very one her corpse/manikin was wearing earlier in the film.

Each of these characters demonstrate that genetics is a way to repeat history and try to revise it, although none of these revisions are successful. Eventually, Shilo makes her own path away from these toxic figures, but she still must reconcile her father’s horrible actions with her own path.

Shilo is just one of the genetic lines in the film. The Largo children are a disappointment to Rotti because they are not exactly like him. He believes that they are a disgrace not because they are violent, but because they act without his permission. In other words, they consistently disobey their father and act independently throughout the film, the same independence which Nathan worries Shilo will develop.

It is additionally interesting that although we see two father figures, and one heavily fixated mother figure, we never uncover the Largo children’s mother. For a film so fixated on the relationship between parent and child, it is strange that we don’t learn anything about her. It is as though Shilo’s mother was the only mother Largo’s children had. Each of them was born before Shilo, which suggests that they became her surrogate children, before she eventually abandoned them to have Shilo with Nathan. This might explain why the Largo children are constantly looking for ways to fix themselves, to be fulfilled, and to control the people around them, as they weren’t enough for Marni to stay. Luigi murders, Pavi is a sex addict and wears different people’s faces, and Amber undergoes constant surgeries. Alternatively, perhaps their unstable nature reflects their unclear genetic history, as they don’t mirror Rotti, and therefore, unlike Shilo, they have no narrative to repeat or to avoid and are lost as a result.

“Stories Often Outlive Their Authors, Especially the Good Ones”

The two Devil’s Carnival films pick up on many of the issues highlighted by Repo, particularly the concept of independence. Not only do they explore if human nature is set or if we make our own decisions, but they outline this discussion using classic literature. By framing modern problems using Aesop Fables, the films suggest that our behaviour is pre-decided with only a few possible outcomes, and that very few of us ever escape from these Aesop fable lessons. This extends Repo’s discussion around genetics, as the sinners must consider whether they were always going to be sinners because of fate or if they had some agency in that route. This essentially boils down the politics around responsibility, the old ‘devil made me do it’ scenario. Sinners must consider if they deserve to be in Hell because they did something wrong, if that wrong was avoidable, or if they were judged too harshly by both themselves and the divine systems.

Much of the narrative in the first Devil’s Carnival is an adaptation and commentary on the more well-known Aesop Fables. By using these older stories, the film implies that humans will always repeat the same scenarios, and however unique a person’s situation might seem, they ultimately return to one of these moral systems. For example, the film uses the “Scorpion and the Frog” to discuss one of the deadly sins: sloth. We typically think of sloth as being lazy, but Devil’s Carnival suggests it is also when a person never bothers to act or think for themselves, or to critically think about their behaviour and other people’s. In the original story, a Scorpion asks a Frog for a ride across a river. Halfway across, the Scorpion pricks the Frog, paralyzing it and drowning them both. As they slowly descend, the Frog asks the Scorpion why he pricked her when he knew it would lead to both of their deaths. The Scorpion explains that pricking things is in its nature, regardless of the consequences. The moral is supposedly that certain destructive people will always be destructive even when they are self-aware and when it leads to their own self-destruction. It is in their nature to do so.

In the context of The Devil’s Carnival, the “Scorpion and the Frog” is retold through a toxic relationship. Tamara arrives in hell after she was killed by her abusive boyfriend, but when given the opportunity to change her ways, she repeats herself and falls in love with a different Scorpion. She gives in to her trusting nature and is stabbed, or pricked, because of it. Her death suggests that the moral around the original story applies to both the Frog and Scorpion. Although it is in the Scorpion’s nature to prick, it is in the Frog’s nature to trust the Scorpion. Tamara must take responsibility for her naivety and learn to make her own way across the river. It is noteworthy that the Frog doesn’t need the Scorpion to cross the river, he needs her, and she carries the Scorpion because he asks. Like the frog, Tamara must realize that she can survive on her own.

I do have trouble with this reading in the film, it turns to victim blaming, although arguably the film suggests that Tamara doesn’t deserve hell, but rather, this is an unjust system where Heaven is the one victim blaming. Then again, unlike the Aesop fable, the Scorpion survives here, and the carnies spend a whole song poking fun at her, so what might that suggest? Tamara is also explicitly sexualized in the same light during the after-credit song, “In All My Dreams I Drown”, which suggests that the Devil is a third Scorpion, in addition to her boyfriend and the carny. It’s noteworthy that she doesn’t appear in the film’s sequel, which doesn’t bode particularly well. This sexualization is a common criticism for both Repo and Devil’s Carnival, as both rely on extreme male gaze in moments, and while sometimes this lends to the comedy and bizarreness of these worlds, and the projects’ criticism/satire, there are some uncomfortable and inappropriate moments in these films, fandoms, and sets. I still think they are interesting films, but also that this is an important criticism.

“Let Us Remember the Past So We May Better Destroy the Future”

Hell gives each sinner the opportunity to improve themselves or to turn away from self-pity, perpetuation, and grief. Ms. Merrywood gambles everything just in case she can get a greater prize. John refuses to deal with the death of his son, and disregards everything around him. Only by rejecting these Aesop patterns can they ascend to heaven. John is let into heaven at the end of the film because he stops grieving and changes his behaviour. This implies that all souls can be redeemed if they can stop their habits, but much like Repo, The Devil’s Carnival suggests that human nature is almost impossible to escape from.

The second Devil’s Carnival illustrates that Heaven is not a splendid and carefree place. Souls must earn their wings and are often tortured and overworked by the complex system in Heaven. While Hell punishes its sinners, it also accepts them as they are rather than enforcing perfection, as Heaven does. God in Alleluia! The Devil’s Carnival is a corrupt figure who abuses his creations, and the Devil is a living example of this exclusionary tactic. God hates personal and physical imperfection and suggests that someone’s appearance is connected to their internal state. This is another connection between Repo and the Devil’s Carnival universe, as both emphasize that we are judged on the relationship between inside and outside. Each film critiques this perspective by suggesting that humans are inherently imperfect and will always struggle with the boundaries between inside and out. The films highlight inside and out by focusing on different examples of intake and expulsion – between heaven and hell, drugs and withdrawal, behaviour and genetics/fate.

“We Started this Opera Shit”, or Did We?

Repo and The Devil’s Carnival are obsessed with breaking tradition while also paying tribute to these traditions. They are a new kind of opera, but one which returns to the outlandish and operatic situations and conventions. They are a new horror musical, but also one which returns to the actors of several famous horror musicals. These films are thus a type of recycling, a modified body. They incorporate the parts and aesthetics of earlier works while also reshaping them into new and frightening outcomes. As a result, both the subject and form of these films reflects the issues around genetics, that unavoidable narrative which haunts our behaviour and impacts our understanding of the world.

The characters in Repo are governed by their genetics, but they eventually form new narratives on their own. The sinners in The Devil’s Carnival films repeat the same Aesop morals until they eventually break free from this unfair moral system. I would argue that the structure of these films does the same, as they return to these earlier works, actors, and associations, and make them their own. While these three films didn’t create these conventions, they expand the horror and opera genres while also directing their audiences to the broader politics around genetics, responsibility, and rebellion. What makes Repo and The Devil’s Carnival series so unique is thus their ability to modify pre-existing cinematic bodies into new shapes while also critiquing this form of modification.