Updated August 29th, 2021.

Little Women argues that romance is a luxury, while marriage is a practicality. As the March sisters’ experience, both positions have good and bad connotations. Today however, I want to focus on the way love becomes a label in the 2019 film, and how characters like Amy are conscious of that label and women’s role in society.

What is a passive character?

It is easy to claim that a female character is passive, meaning she is either a victim or someone who never objects to her placement in a patriarchal society or relationship. The term ‘passive’ has become a bit of a blanket term we use to describe traditional women, especially those who serve no narrative purpose other than to be a love interests or moral compass. This is not a new convention; we have seen it in everything from poetry to film. Women often appear only as the object of someone’s affections, and we never hear from their perspective. This begs the question, how might a ‘so-called’ passive woman interpret the world? Do they resist these conventions in any way? Or is the ability to outright resist this imposed status as much of a luxury as imposing those conventions in the first place, a luxury held by men and domineering institutions?

One of the defining features of a passive woman is her unconscious nature, or her inability to see the governing ideologies and structures which consistently suppress her. At the same time, because we so rarely hear from passive women in these projects, it is difficult to measure just how unconscious they are. This implies that the term ‘passive’ is just another form of suppression, one which places women into an inhuman and unthinking category.

I have always been drawn to finding gaps in older male dominated narratives, specifically moments where a woman can assert her opinion, even in the quietest of ways. I think it is important to acknowledge the risks involved with outright declaring and resisting. Making huge displays is dangerous, then and now, and has political and judicial consequences. As such, little expressions and rejections are one-way women can act without people noticing, and that should not be dismissed.

What I mean to say is that there can be layers of resistance within passivity, and I think Amy from Little Women is a perfect example of this.

Reading Amy

Amy is traditionally read as an annoying child who is unaware and uncaring of her surroundings. It is hard to forgive her for burning Jo’s novel, among other things. Yet, the 2019 version of Little Women did the seemingly impossible by making Amy a complex and sympathetic character, one who is perhaps more level-headed and conscious than her sisters.

Amy is studying to be an artist in Europe. That alone is an unusual thing for a woman of the era, as even in the 19th century, painting was a largely male activity. Female painters were expected to create feminine images, those with flowers and pastoral themes. Amy does something different because she is aware of these conventions. She consciously performs passivity and femininity to help her family and herself. This awareness is a crucial aspect to Amy’s characterization in the film, as she is not a weak individual but one who is smart enough to recognize the expectations of how she should act, and the little ways in which she can assert her independence in this patriarchal world.

When Laurie visits Amy’s studio, he is surprised to find how pessimistic she is about her artistic potential, and her plans to marry rich. Laurie comes from an ignorant perspective, something which Amy lectures him about in the scene. In a silly attempt to comfort Amy, Laurie asks, “What women are allowed into the club of geniuses anyway?”. I think what Laurie is trying to suggest is that genius is a masculine activity, one which women have little time or talent to follow. Amy has no patience for this ridiculous claim, and the rest of the scene is her attempt to school Laurie on his privilege.

Laurie asks who is a genius rather than asking why, and that is exactly the problem. He is interested in specific examples which he would have heard of, but as Amy suggests, that only perpetuates the masculine versus feminine model. The reason neither Amy nor Laurie can identify women geniuses is because they are rarely spoken about. It is not that they do not exist, just that they are not celebrated. Their work is either suppressed or quietly controversial, so much so that it is difficult to find.

What makes Laurie’s claim ironic is that it reflects the very nature of the book and movie. Both the novel and film were created by women; Louisa May Alcott and Greta Gerwig. This suggests that female genius is all around the characters in the film, permeating every scene. The fact that Laurie is unconscious of this state speaks further to the invisible (or little) women motif found throughout the narrative.

Gerwig and Alcott imply that although these women are ‘little’ in the eyes of society, as is their work, it is only ‘little’ when compared to loud declarations and displays of patriarchal power, power which they have little access too.

Later in the scene, Amy notes that she is “of middling talent”, which I think is evocative of her character. She says this in response to Laurie’s comment about women’s versus men’s talent, with Amy claiming she is between these positions. This implies that Amy is similarly between these perspectives and is thus caught in a binary between the two. Amy is aware of the expectations faced by men and women, and uses this perspective to make her way in the world. She belongs to neither party completely, as her work and life is strung in the middle, operating between the two labels.

Amy is done with Laurie’s privileged view of love and marriage. As she explains, marriage has nothing to do with love. It is a smart economic proposition which she has little choice of. Unlike her sisters, Amy seems to be the only March family member to understand the bleak role of women in her position. She notes, “as a woman, there is no way to make my own money”, and that any property or children she has would belong to her husband. That is horrific, and it’s something Laurie knows but doesn’t want to think about, because he doesn’t have to.

Setting and Camerawork as Extensions of Amy

As she says this monologue, the camera work changes to emphasize her position in the center of the frame. We don’t see Laurie during this speech, just Amy. The camera slides towards the foreground as Amy walks forward, almost threatening to enter our realm. The smooth camera glide and Amy’s placement suggest two things: that she is saying something monumental and that she is talking directly to us. Amy’s speech is a defense against Laurie’s claim, that she is passive and loveless, but it is also a defense for passive women, those who are just trying to survive.

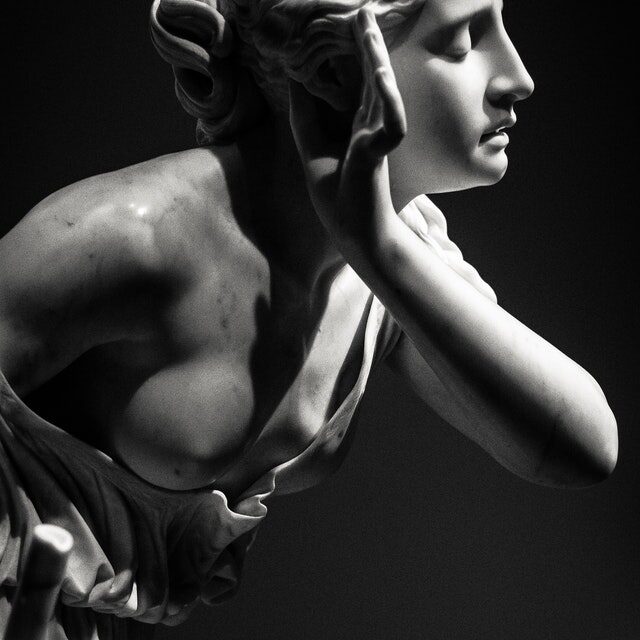

The setting of this speech makes Amy’s assertions more powerful. We are at Amy’s studio, a place where she is in control can render life in whatever way she chooses. Despite this artistic freedom, Amy is surrounded by idealized statues of women, especially those who are missing body parts. We see the famous Nike Victory statue in the background, one without a head, and multiples statue without arms. These objects represent the fragmented female body, the bits and pieces which are singled out and idealized but also abused (cut apart). Even if Amy is sharing the studio with other artists, this is the environment through which she creates. She is surrounded by cut women, well aware of how their idealization hinges on their half state. Silent and fixed, in other words, passive.

There is one painting which stands apart in the scene, the portrait behind Amy’s shoulder during her speech. When I first saw the film, I thought that it was a painting of Mary Wollstonecraft, one of the more prominent and outspoken feminist authors of the 18th century. I don’t have confirmation on that, and the portraits do look different after a second screening, but for whatever reason that impression has stayed with me. I know I have no grounds to make this comparison, yet here we are. The idea that Amy has this powerful and loud figure on her shoulder while lecturing about the suppressive role women face is profound. It makes her line “I’m not a poet, I’m just a woman” more effective. Unlike the romantic era poet, Amy does not have the luxury to roam the world and complain about love. She has more important things to do, especially as women are traditionally the subject of these poems, not the authors. So, while Amy is not happy about her restricted position, she also has no patience for people who pretend that such conditions do not exist, as Laurie does.

Amy’s art extends beyond the canvas and into the way she performs herself. When she is with Laurie, she becomes more comfortable and willing to talk about her life and beliefs. But, as she leaves the scene to meet with Fred, she takes off her painting apron and puts on a pretty cloak. This move suggests that Amy must leave behind this artist environment and return to a world where she is the ornament, not the creator. This moment also says something about her confidence around Laurie, as by drawing him, Laurie is subject and she the artist. When she puts on the cloak, Amy moves back to her ‘so-called’ passive position and begins to consciously perform femininity.

It is additionally noteworthy that Amy’s speech was written by Gerwig on the day of filming. Meryl Streep actually suggested it, as she felt that modern audiences and girls needed some explanation for why Amy was upset with Laurie. Love is not the central theme of the scene, privilege is. Laurie is wasting opportunities from his wealth and family, opportunities which Amy does not have the same access to. Her speech is thus a condemnation of ignorance, specifically the kind which suggests that women are not aware of what is happening around them, and that they are not in control of their own minds. As Amy demonstrates, it is not that they are not aware, but that their thoughts, lives, and actions are labeled ‘little’ by society. However, as Amy and her sisters also illustrate, it is in this ‘so-called’ littleness that greatness is found.